Ahmed Harara is a dentist. While protesting during the Egyptian revolution in January, Harara was struck in the eye by a rubber bullet. Blinded in one eye, he continued protesting. Then during the most recent protests in Tahrir Square, Ahmed was shot in his other eye by a rubber bullet. Now he is completely blind.

But he kept protesting.

Ahmad is one of more than a hundred protestors around the world photographed by TIME contract photographer Peter Hapak. From Oakland to New York, and across Europe and through the Middle East, Hapak and I traveled nearly 25,000 miles and photographed protesters and activists from eight countries.

We photographed protesters representing Occupy Wall Street, Occupy Oakland, Occupy the Hood, the Indignados of Spain, protesters in Greece, revolutionaries in Tunisia and Egypt, activists from Syria fleeing persecution, a crusader fighting corruption in India, Tea Party activists from New York, a renowned poet-turned-protestor from Mexico, and a protestor from Wisconsin who carries a shovel, topped by a flag.

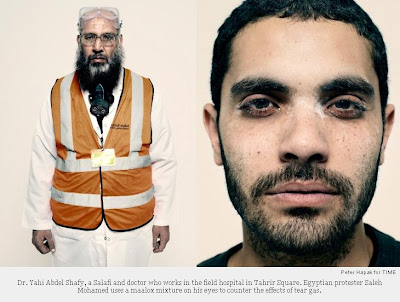

We set up makeshift studios in hotel rooms, inside apartments and peoples homes, inside a temple in rural India, an anarchist headquarters in Athens, even in the courtyard of the home of Mannoubia Bouazizi, the mother of Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi. Tear gas wafted into our makeshift studio inside a hotel room overlooking Tahrir Square—the same room Yuri Kozyrev made the now-iconic photograph of the crowd.

Each time we asked subjects to bring with them mementos of protest. Rami Jarrah, a Syrian activist who had fled to Cairo, brought his battered iPhone. He showed me some of the most intense protest footage I’ve ever seen on that broken screen. A Spanish protester named Stephane Grueso brought his iPhone also, referring to it as a “weapon.” Some young Egyptian protesters brought rubber pellets that had been fired at them by security forces. Another brought a spent tear gas canister. Some carried signs, flags, gas masks (some industrial ones, some homemade, like Egyptian graffiti artist El Teneen—his was made from a Pepsi can). A trio of Greek protesters brought Maalox. Mixed with water, sprayed on their eyes to counter the harsh effects of tear gas. Molly Catchpole, the young woman from Washington, D.C. who took on Bank of America – and won – brought her chopped up debit card. Sayda al-Manahe brought a framed photograph of her son, Hilme, a young Tunisian man killed by police during the revolution. El General, the Tunisian revolutionary rapper, brought nothing but his voice – he rapped a capella for us (we have a video). Lina Ben Mhenni, a blogger from Tunisia and Nobel Peace Prize contender, brought her laptop. She was speaking Arabic yet we understood the words “Facebook” and “Twitter.”

Each subject was photographed in front of a white or black background – eliminating their environments but elevating their commonality to that of “Protester,” a fitting set up for a group of people united by a common desire for change.

“They were all unhappy, they wanted change and they wanted better life,” Hapak said. “Everybody is out there to unite their power for one common cause, one common expression—to get a better life”

Patrick Witty is the International Picture Editor at TIME.

Peter Hapak is a contract photographer for TIME, who most recently photographed Tilda Swinton in the December 19, 2011 issue.